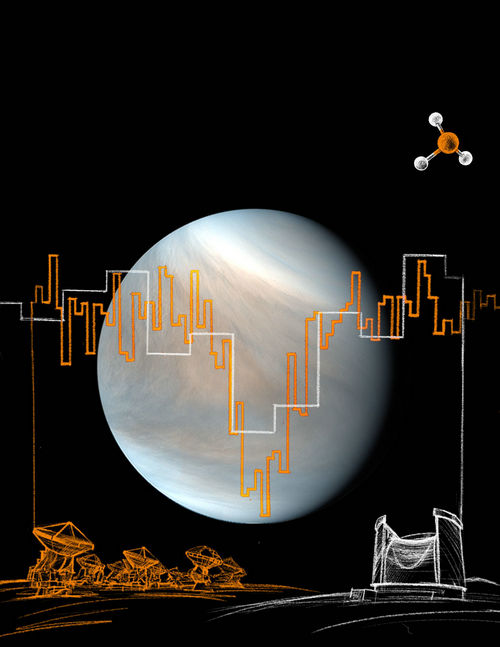

Venus the phosphine molecule and the phosphine detection by JCMT (white) and ALMA (orange) [IMAGE: JOANNA PETKOWSKA]

An international team of astronomers, led by Professor Jane Greaves of Cardiff University, UK, on September 14 announced the discovery of a rare molecule — phosphine — in the clouds of Venus. On Earth, this gas is only made industrially, or by microbes that thrive in oxygen-free environments.

The detection of phosphine, which consists of hydrogen and phosphorus, could point to extra-terrestrial “aerial” life. “When we got the first hints of phosphine in Venus's spectrum, it was a shock!” said Greaves, who first spotted signs of phosphine in observations from the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii.

Astronomers have speculated for decades that high clouds on Venus could offer a home for microbes — floating free of the scorching surface, with access to water and sunlight, and capable of tolerating very high acidity. The new discovery is described in a paper published in Nature Astronomy on September 14.

The first detection of phosphine in the clouds of Venus was made using the JCMT in Hawaii, which is operated by the East Asian Observatory on behalf of CAMS-CAS (NAOC, PMO, and SHAO), NAOJ, KASI and ASIAA. The team were subsequently awarded time to follow up their discovery with the 45 telescopes of the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. Both facilities observed Venus at a wavelength of about one millimeter, much longer than the human eye can see — only telescopes at high altitude can detect it effectively. “In the end, we found that both observatories had seen the same thing — a faint absorption at the right wavelength proved to be phosphine gas, where the molecules are backlit by the warmer clouds below,” said Jane.

The astronomers then ran calculations to see if the phosphine could come from natural processes on Venus. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) scientist Dr. William Bains led the assessment of natural ways to make phosphine. Some ideas included sunlight, minerals blown upwards from the surface, volcanoes, or lightning, but none of these could make anywhere near enough of it. Natural sources were found to make at most one ten thousandth of the amount of phosphine that the telescopes saw. In contrast the team found that in order to create the observed quantity of phosphine on Venus, terrestrial organisms would only need to work at about 10 percent of their maximum productivity. Any microbes on Venus will though likely be very different to their Earth cousins. Earth bacteria can absorb phosphate minerals, add hydrogen, and ultimately expel phosphine gas.

JCMT opens for morning observing with the shadow of Maunakea evident behind as it rises over Hualālai. JCMT is able to observe during the daytime as it operates at sub-millimeter wavelengths. [IMAGE: TOM KERR]

Team member and MIT researcher Dr. Clara Sousa Silva had thought about searching for phosphine as a ‘biosignature’ gas of non-oxygen-using life on planets around other stars, because normal chemistry makes so little of it. She comments “Finding phosphine on Venus was an unexpected bonus! The discovery raises many questions, such as how any organisms could survive. On Earth, some microbes can cope with up to about 5 percent of acid in their environment — but the clouds of Venus are almost entirely made of acid.”

The team believes this discovery is significant because it rules out many alternative ways to make phosphine, but they acknowledge that confirming the presence of “life” needs a lot more work. Although the high clouds of Venus have temperatures up to a pleasant 30 degrees centigrade, they are incredibly acidic — around 90 percent sulphuric acid — posing major issues for microbes to survive there. Professor Sara Seager and Dr. Janusz Petkowski, both at MIT, are investigating how microbes might shield themselves inside scarce water droplets.

The team is now eagerly awaiting more telescope time to establish whether the phosphine is in a relatively temperate part of the clouds, and to look for other gases associated with life. This result also has implications in the search for life outside our Solar system.

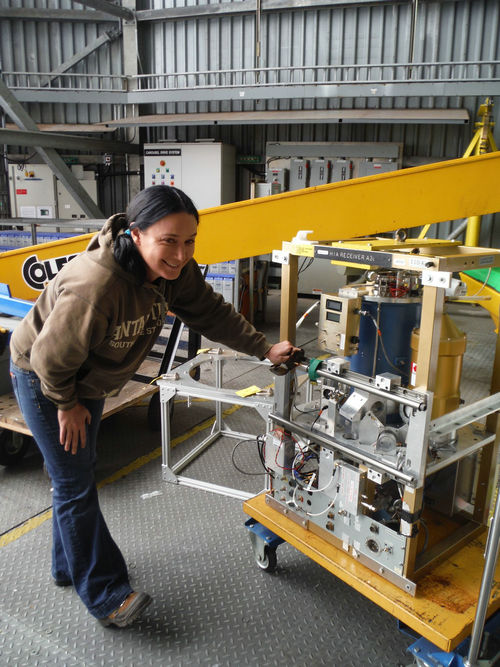

On hearing the results of the JCMT study, the JCMT’s Deputy Director Dr. Jessica Dempsey said “These results are incredible” and went on to say “this discovery made in Hawaii, by the JCMT, was made with a single pixel instrument. This is the very same instrument that also took part in capturing the first image of a Black Hole, Pōwehi. The discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus really showcases the breadth of cutting-edge research undertaken by astronomers using the JCMT. I am so pleased by the efforts from all our staff here in Hawaii.”

The JCMT instrument that captured the phosphine discovery has since retired and been replaced by a new and more sensitive instrument known as Nāmakanui. On the potential of this new instrument, Jessica commented “Like its namesake, a big-eyed fish hunting food in the dark waters, we will turn the far more sensitive Nāmakanui back to Venus in this hunt for life in our universe. This is just the beginning, and I've never been more excited to be a part of our boundary-pushing JCMT team.”

JCMT Deputy Director Jessica Dempsey stands beside the now retired instrument, RxA3m, that made this first detection of phosphine on Venus. The instrument has since been replaced by a more powerful instrument called Nāmakanui that is available to all EAO astronomers. [IMAGE: HARRIET PARSONS]

With a diameter of 15m (50 feet), the JCMT is the largest single dish astronomical telescope in the world designed specifically to operate in the submillimeter wavelength region of the electromagnetic spectrum. The JCMT is used to study our Solar System, interstellar and circumstellar dust and gas, evolved stars, and distant galaxies. It is situated in the science reserve of Maunakea, Hawaii, at an altitude of 4,092m (13,425 feet).

The JCMT is operated by the East Asian Observatory on behalf of CAMS-CAS (NAOC, PMO, and SHAO), NAOJ, ASIAA, KASI, as well as the National Key R&D Program of China. Additional funding support is provided by the STFC and participating universities in the UK and Canada.

For more information, please contact:

Dr. Jessica Dempsey

Email: j.dempsey@eaobservatory.org

James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, East Asian Observatory

Source: James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, East Asian Observatory