A series of scientific satellites, including one to probe dark matter, will be launched over the next two years, said Wu Ji, director of the National Space Science Center under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

The development of the four scientific satellites is going well, Wu said recently at an event marking the 10th anniversary of cooperation between China’s Double Star space mission and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Cluster mission to investigate the earth's magnetosphere.

The first satellite, the dark matter particle explorer, will be launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwest China at the end of this year. All major tests and experiments have been completed, and a mission control center for scientific satellites has been set up in Huairou, northern suburb of Beijing, Wu said.

The dark-matter particle explorer will observe the direction, energy and electric charge of high-energy particles in space, said chief scientist Chang Jin.

Chang also said that it will have the widest observation spectrum and highest energy resolution of any dark-matter probe in the world.

Dark matter is one of the most important mysteries of physics. Scientists believe in its existence based on gravitational evidence, but have never directly detected it.

China will also launch a satellite for quantum science experiments next year. “It’s very difficult to develop the payload of the satellite. We have overcome many difficulties in making the optical instruments and are confident of launching it in the first half of next year,” Wu said.

China's dark-matter particle explorer satellite (China Features)

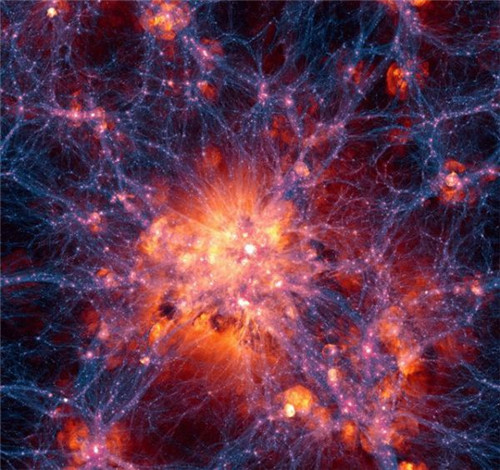

This image, provided by the Illustris Collaboration in May 2014, shows dark matter density overlaid with the gas velocity field in a simulation of the evolution of the universe since the Big Bang. (AP Photo/Illustris Collaboration)

A photo from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope released on April 13, 2015 by the European Southern Observatory shows the rich galaxy cluster Abell 3827. The strange blue structures surrounding the central galaxies are gravitationally lensed views of a much more distant galaxy behind the cluster. (AFP Photo)

A retrievable research satellite, SJ-10, will also be launched in the first half of next year. It will carry out research in microgravity and space life science to support manned space missions.

The satellite is expected to carry out 19 experiments in fluid physics, combustion, space material science, space radiation, and space biology.

Eight experiments in fluid physics will be conducted in the orbital module, and the others will be conducted in the re-entry capsule, which is designed to return to earth after 12 days in orbit. The orbital module will keep operating in orbit for three more days.

The SJ-10 project was jointly developed by 11 institutes of the CAS and six Chinese universities in cooperation with the ESA and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Next year’s launch schedule also includes a hard X-ray telescope, which will observe black holes, neutron stars and other phenomena based on their X-ray and gamma ray emissions.

Wu said that since the space era began in 1957, the United States and the former Soviet Union have made 90 percent of the “firsts”. In recent years, Europe and Japan have also made great progress. The first landing on Titan and the first landing on a comet were accomplished by Europe’s Huygens mission and Rosetta-Philae mission; and the first mission to take an asteroid sample back to earth was made by Japan.

"But we didn’t hear any Chinese voices in those great missions. China is the world’s second largest economy, and a major player in space. We should not only be the user of space knowledge, but also be a creator," said Wu.

"China should not only follow others in space exploration; it should also set challenging goals that have never been done by others, such as sending the Chang’e-4 lunar probe to land on the far side of the moon."